Travel in Tibet – an eye witness account of real occupation

Deciding to travel to Tibet was not an easy task. I normally take as much delight in planning my trips as I do in the travel itself, but this decision was a moral one. If I was to go, would I be supporting the Chinese regime and condoning their occupation of the land and inhumane treatment of Tibetans, but on the other hand I wanted to see for myself in order to try to help spread the word about the reality of the situation in this beautifully desperate Himalayan country. Eventually we decided to visit for three days at the end of our trip to Nepal and were lucky enough to get the visas approved (we met a lot of people who were not).

The one-hour journey was a little fraught, in a tiny bumpy plane over the Himalayas, with thick cloud unfortunately obscuring Everest (although we did spot it on the way back). The fun and games with the Chinese started immediately on arrival, before we could even acclimatize to the altitude. We lost count of the number of times we had to show our passports (a frustration I also encountered when travelling into Palestine) and my companion had her reading material confiscated – although in hindsight, taking Seven Years in Tibet across was probably not the most sensible thing to do. We just hadn’t expected our hand luggage to be searched so thoroughly – all reading material and papers were scanned, photos were checked (including those in the books) and we were questioned as to the subject of the books we were reading. When Seven Years was confiscated we argued with the soldier, and were informed “it’s not allowed”, we weren’t giving up without a fight but when we continued arguing we were told the reason it was not allowed is because “it isn’t real” – this is when you realise it is pointless to keep arguing with such ignorant, brainwashed individuals.

Unfortunately our itinerary was limited to the city of Lhasa – the Chinese are the ultimate control freaks here, they may have given us the visas but we were strictly controlled in terms of where we were allowed to go, with whom and when – we had to follow the itinerary to the letter. So, aside from a little spot on the way from the airport which had some beautiful Buddhist carvings into the mountain and paintings of the ladders which take you to heaven, we were limited in our views of the country.

The landscape on the journey was desolate and barren but in a pretty kind of way, certainly preferable to the city of Chinese neon which greeted us at Lhasa. Our arrival was marked by the first of many army checkpoints meticulously studying our driver and guide’s papers – I hadn’t expected to see quite so many army and police in one spot, it looked ridiculous among the crowds of wizened old Tibetan pilgrims performing circumnavigations of the temples in the old town.

The Hotel Mandala was nothing special but had a fantastic location right in the centre of the old town, overlooking Jokhang Temple, which meant we didn’t have to wander far at night for something to eat – a blessing in those temperatures!

Unfortunately we had not been able to do much research as there is no literature on Tibetan history and heritage available in the country and the guides are not supposed to say too much as people are often eavesdropping. This made the sightseeing somewhat frustrating, our guide was great and shared as much as he could, but there were obviously times he held back or simply explained that he could not answer our questions – it was heartbreaking but we didn’t want him to get into trouble and with all the cameras everywhere and potential ‘spies’, we decided not to push further.

The iconic Potala Palace was breathtaking (literally as you ascended to it at 4,000m!) The interior was incredibly atmospheric, dark and smoky, with monks chanting in corners. The melancholy feeling was as strong as the incense, that the rightful home of the Dalai Lama should sit empty and welcoming hordes of Chinese tourists, having their heads filled with inaccurate information.

Jokhang Temple was equally impressive, in fact I cannot even find the words to describe it – like being inside a mystical, intricately decorated cave. Unfortunately we were not allowed to take pictures at either of these holy sites, although I don’t think these would have done them justice, it was more the feeling, smells and sounds that have been etched in my memory. We did get some nice pictures from the roof of the temple, although we were closely watched by the guards and I was told off every time I tried to get pictures of the hordes of troops collecting in the old town square with their unecessary riot shields and radios. Interestingly, we didn’t take any of the typical posed tourist photos while in Tibet, it just didn’t feel right – we were there to witness and document the situation and whilst the sites were awe-inspiring, we weren’t comfortable with the wider situation and therefore it didn’t feel right to make light of this.

My favourite location however was Tsamkhung nunnery, meaning meditation cave in Tibetan. This is a natural cave that was established as a nunnery in the 15th century and is the only nunnery inside the city of Lhasa. It was the one place we saw that doesn’t have to pay tax to the Chinese government and as such it was the one place we felt comfortable buying souvenirs and gifts from, knowing that the cash would not be directly lining the pockets of the Chinese occupiers. The nuns were so friendly without words, we watched them rolling their scriptures and praying, and met a very sweet 86-year-old nun living there.

Drepung Monastery is located 10km out of town, it’s the biggest monastery in Tibet with six temples, three monastic colleges for the study of philosophy and one for the practice of Tantric Buddhism, all totalling over 20,000 square metres. The monastery used to be home to 10,000 monks, although sadly it now only houses 400. The site was huge and beautifully white washed with a huge medieval looking kitchen, which unfortunately is now only half used.

The penultimate stop on our limited tour was Sera Monastery, the second biggest monastery in Tibet, with an assembly hall, three colleges and thirty-three houses. Here we joined worshippers in bending down and touching our foreheads onto the cloth of the protector and also got blessed by a monk – we had to pray with our head leaning on his stick, while young children all got their noses smudged! The monastery is most well-known however for its debating monks, we sat for some time watching them in their groups outside, it was an incredible experience, without being able to understand a word – so much shouting and hand slapping! The monks live a simple life abiding by four rules from what we could ascertain: Never marry, never tell a lie, don’t kill animals and don’t steal.

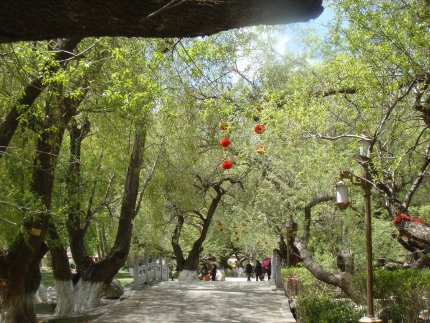

The final destination of our official tour was Norbulingka, translated as Jewel Park, the summer palace of the Dalai Lama and the place he was forced to flee from when the Chinese invaded, and now a World Cultural Heritage Site and venue for annual Tibetan festivals. The palace itself was very ornate and pretty and was surrounded by beautifully landscaped royal gardens with trees, flowers and lakes and intricately designed and brightly decorated buildings.

The food we ate mostly consisted of yak – I tried everything from yak ribs to good old yak momos, and the stomach-churning yak butter tea, the likes of which I have never tasted before (and hope to never taste again!) It was like drinking melted butter – I guess it must grow on you, but for our un-aquired tastes we stuck with the much tastier sweet milk tea as a warmer. Makye Ame and Mandala Restaurant were our preferred places to rest in the warm – cute little places with good food, although the melancholy spirit that shrouded the city (country?) even pervaded here. On our final night we were convinced to visit the Mad Yak restaurant for a traditional Tibetan buffet and cultural show – it was very commercial and not my usual thing, but our guide was so keen for us to go and see the dancing that we relented – in fact I was even convinced to try sheep’s lung, and was dragged up to dance with the oversized and brightly coloured yaks, yetis and other mythical beings!

On our final afternoon in Tibet our guide and driver decided to break the rules and take us off the itinerary – to visit the drivers home in his village! We were so touched to be invited, especially given the potential consequences, and we were honoured to get more of an insight into such a lovely, strong people. Sadly, all of the plains and fields that used to surround the villages have been converted into Chinese shops and so these villages have now been swallowed up in the sprawl of Lhasa. This has meant that the villagers have had to turn from their centuries-old traditions of farming, to labouring and construction, and get rid of all their animals. The driver’s family were very hospitable, even though none of them, including the driver, could speak any English! We were served traditional barley beer which has a strict drinking ritual of dipping the fourth finger in three times then sipping three times before downing the drink. I wish there could have been more as the next drink to be served was the ominous yak butter tea – only this time we could not refuse! I made the stupid decision to drink it very quickly and be done with it, what I hadn’t realised was that once the cup is empty it’s a sign to be refilled – and I therefore had twice as much to try to stomach, washed down with fruits, sweets and yak jerky! They showed us their traditional thangka arts and prohibited pictures and photos of the Dalai Lama that were hidden away (anyone displaying images of the Dalai Lama in their homes can go to prison for 15 days!) and also explained that all of the furniture is new, replicas of the traditional items, as these were all destroyed during the Chinese ‘Cultural Revolution’. We were so sad finally hearing a little of the history from the horse’s mouth – none of them have passports and as such our guide has not seen half of his family for many years as they left before the ‘liberation’. Tibetans also have the number of children they are ‘allowed’ capped, which is completely against all Tibetan family traditions, whilst the Chinese are encouraged/incentivized to have as many children as possible! This also leads to issues with access to education and employment as Chinese youths are favoured. We felt so helpless but the guide explained the best thing for us to do was to try to find Tibetans in our own countries and try to help them, and try to spread the word internationally. We gave the wife our scarves as a parting gift as this was all we had, while we were given little protective talismans to keep us safe, and were then driven back by the son, as our driver had gotten a little carried away with the barley beer in the excitement! To finish up the day, we went for a massage at Tenzin Blind Massage Centre, an establishment set up by Braille Without Borders that employs blind Tibetans so that they can help make a living for themselves. The teenage girls that we had as therapists were very sweet and gave fantastic massages, even if they were a little shy.

The trip felt like a lot longer than three days, and although it had been an eye-opening experience and we had witnessed some magical places and met some amazing people, we left with a deep sense of sadness, perhaps picked up from the air, which was heavy with it. The situation is hard to believe without seeing, which most people never will, and the people of Tibet so desperately need the support of the rest of the world in bringing their cruel and unjust occupation to an end. I hope that opinion changes in the world and that action is taken before there is much more unnecessary bloodshed and destruction of an ancient and sacred civilisation.